Staten Island: The Reformed Church of Huguenot Park

While celebrating its 175th anniversary, a historic church ponders its future.

A little rain is falling, but that does not stop nearly 50 people from attending a BBQ party on the grounds of The Reformed Church of Huguenot Park on the South Shore of Staten Island. Hamburgers and hot dogs are being grilled with soda, coffee, and water available to drink. Inside the church hall, there are salads, cookies, donuts, and other snacks being offered. The atmosphere is vibrant and many families have gathered, the young and the old. Many are wearing purple t-shirts that read “RCHP 175”. It feels like any other big community gathering often seen at many religious places.

Except this isn’t just any community gathering. This church community is marking 175 years of the creation of their congregation. They are also marking 100 years since their congregation’s most recent physical church, a medieval-looking building at the corner of Huguenot Avenue and Amboy Road, was officially dedicated. There is much to be excited about as well as reflect on.

“This is a birthday party for the church,” says Church Elder, Arnie Mattsson. Raised Catholic, he was married in this church over 40 years ago and raised his three children here, all of whom are now adults with their own families. “We knew so many would come. It’s about coming back. Many have moved away to New Jersey and elsewhere.”

It seems with this community moving on and leaving other places behind amid uncertainty, there is an echo of what their ancestors, the French Huguenots, did 350 years ago.

The History

The name Huguenot refers to French Protestants who were influenced by the teachings of Martin Luther and later, John Calvin, which led to the creation of the Reformation Church in France. It is estimated that by the mid-1500s, there were 1.5 million Reformists in France, which did not sit well with the French monarchy and the Roman Catholic Church. A General Edict in 1536 labeled the Huguenots as heretics, and this started many years of persecution of the Huguenots, with some worse than others. Kings Louis XIII and Louis XIV sought to eliminate Huguenot churches and communities, which caused thousands to flee France. Some went to Holland, England, and even the American colonies.

Starting in 1624, Huguenots began to settle in what is now New York. Many settlements struggled to live alongside the native Lenape tribes. But by 1658, more permanent settlements took hold, including on what is now Staten Island. These French Huguenots were free to practice their faith, unlike their home country of France. In 1665, Daniel Perrin settled in the Island’s South Shore and was dubbed “The Huguenot” which is why the neighborhood today goes by that name.

The Building

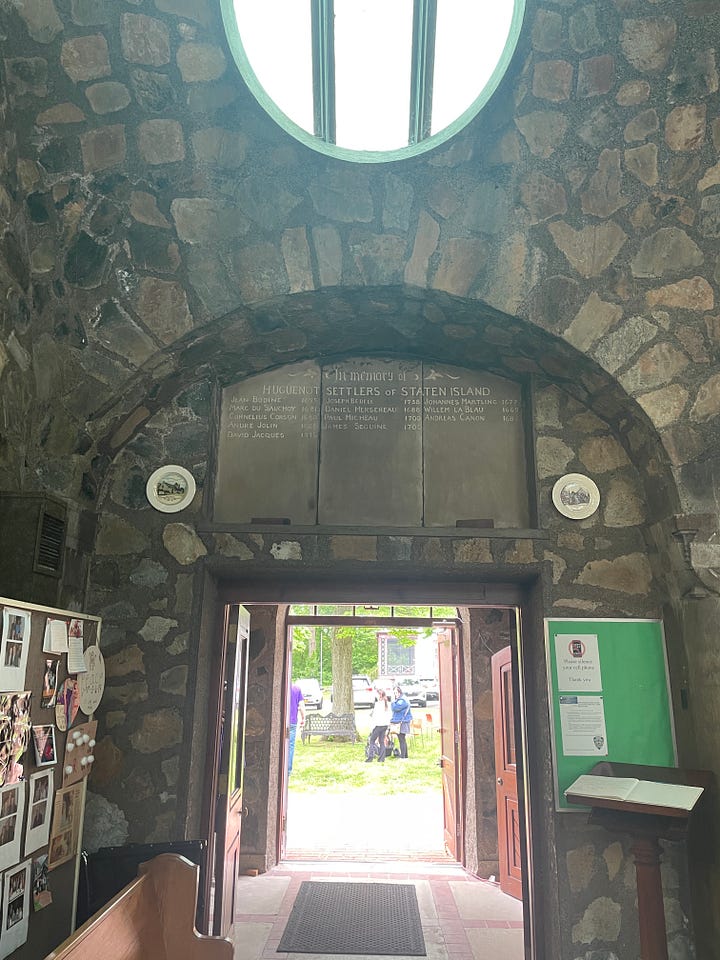

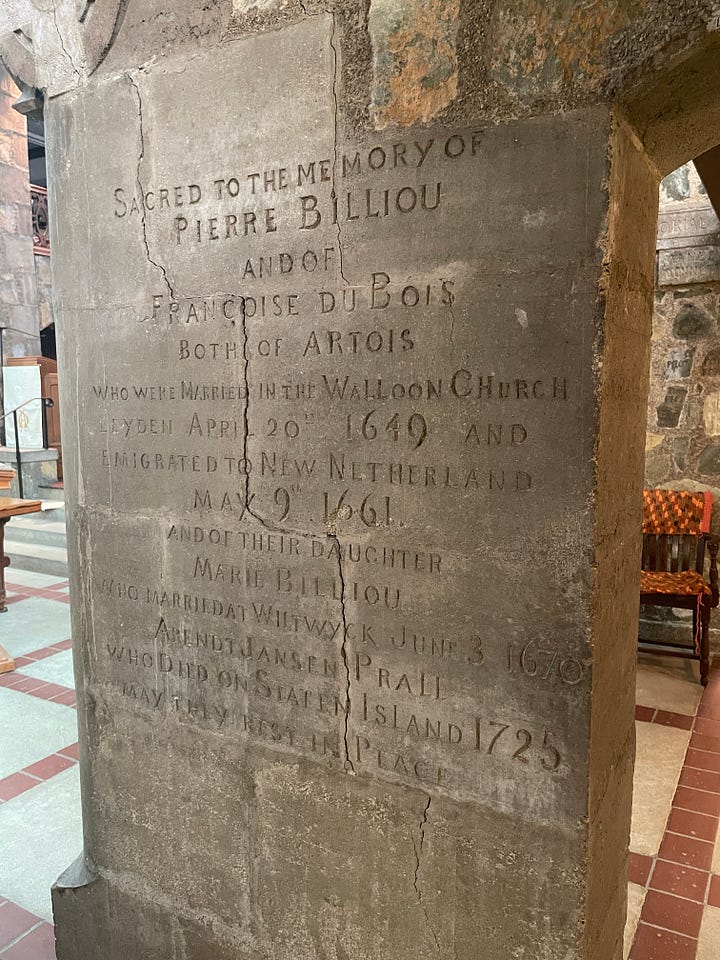

The first French Huguenot Church was built in the late 17th century just north of Perrin’s namesake, and it was shared with Dutch Reform and Anglican congregations. In 1849, a group of Huguenots won approval to build their own church. From then on until 1918, a small wooden church stood where a noted Huguenot, Pierre Billiou, one of the Island’s first sheriffs, owned land; his descendants, the Prall family gave the land to the congregation.

But in April 1918, ember sparks from a nearby train landed on the church’s roof and set it on fire. In March 1924, a new church was dedicated, the one that stands today in a style reminiscent of “vernacular Norman architecture of England and northwestern France”, according to Holden’s Staten Island: The History of Richmond County.

The medieval appearance was made possible by architect Ernest Flagg who used serpentine stone to build the church; it was refurbished in the 1980s. Stained glass windows tell the story of historic Huguenots, among them George Washington whose maternal family included Huguenots. Stone pillars give the information of noted settlers, including Perrin and Billiou. It is even registered as a National Historic Landmark and is both a memorial and a place of worship.

Just like the first place of worship that Staten Island Huguenots attended, this one also allows other churches to hold services. New Life Community Church, a Reform Church of the Korean community after the Huguenot services.

Celebrations and Concerns

Leaders of that church were present for the celebrations and even helped Mattsson say “welcome” in Korean during a celebration service in between the day’s festivities.

Also in attendance is a group of teenagers who attend Tottenville High School, just a few blocks down the road. They are part of Seekers Christian Fellowship, which has clubs in colleges and high schools around New York City. Their leader told the congregation how grateful he is for RCHP to allow his group to meet on its grounds.

“The Bible says we are judged by our faith,” he said. “Faith is passed down to generations, but not enough have passed down.”

This is a sentiment many, particularly older members, were feeling during the celebrations. Mattsson says nearly 200 attended services in the 1980s and 1990s, but now 30 or 40 attend with a few others livestreaming.

“Like any other church, we’re dwindling,” says Bob Laurino. “Folks are dying off and there are few children.”

Mattsson agrees, comparing his church’s struggles to that of the Roman Catholic churches and schools, some of which have closed down in recent years.

“People bring their kids to learn about God,” he says. “Now, they don’t have the time. Grandchildren are being baptized but their parents don’t want to instill or don’t want to create waves.”

Mattsson adds Sundays are lately for flag football and Little League, which also see families travel for meets. He does, though, believe families who once belonged to RCHP as well as other faith seekers, will find their way back to God.

What Lies Ahead

For Reverend Dr. Terry Troia, there is more to being a church than attending services. It is about bringing love to the world as God loves the world.

“Inside, we learn about the Gospel and live it,” she says. “We are equipping people to go out…to heal what is broken, to reach out to the sick, the lonely, and the hungry.”

Reverend explains that her church discusses various racial and social justice issues, including the war in Gaza, race and trauma, and the work the real St. Nicholas did in the 4th century BCE. She points to a banner on the church fence that says all are welcome, be it immigrants, people of all colors, all genders, all orientations, no matter anyone’s economic status. Members of the church attended a vigil recently for an eighth-grade boy who was shot. Rev. Troia says this is what God wants the church to do, and it is helping New Life Community Church to do the same.

“It’s a ripple effect,” she says. “It’s the movement of the Spirit. The church is not a building. The church is you and us.”

When asked if she is concerned about the future of RCHP with its dwindling members, Rev. Troia is fiercely optimistic.

“It will be there,” she says. “Our descendants will carry the mission because of a man who walked in Galilee.”