Brooklyn: Christ Church Cobble Hill & The Brooklyn Zen Center

A Single Building Shared By Two Religions, and Others, Inspires Community and Healing

There’s a church in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn going under reconstruction, but not just on its exteriors.

On the outside, it is easy to notice the scaffolding working on the tower and roof. Walking by the church, on the corner of Clinton Street and Kane Street, however, maybe not all will notice the signs pinned to the green boards that are part of the scaffolds. Whoever does may see something curious.

This church is Christ Church Cobble Hill, an Episcopalian Church built and completed in 1841-1842. According to its website, this is one of the older buildings in continuous use in this section of Brooklyn.

But then there are signs and flyers referring to other groups and organizations, including the Cobble Hill CSA, Bloom Again Brooklyn, Green Faith, Freebird Books, and the Brooklyn Zen Center.

Does this mean an 182-year-old church allows Buddhists into its building to practice their Buddhist faith?

What Reverend Mark Genszler and Sarah Dojin Emerson say, they share the space and co-locate.

In 2012, Christ Church’s tower became unstable and started to collapse; parts of it hit and killed a passerby. The height of the tower had to be reduced, as ordered by the Dept. of Buildings, which was the start of the church’s ongoing reconstruction. It also was the beginning of Christ Church needing new ways to pay its bills.

“There’s this inherited legacy of immense and expensive [maintaining of] buildings and how to view them as resources for the common good,” says Reverend Genszler. “Rather than esoteric places of specific history and practice only.”

Upon hearing that the Brooklyn Zen Center was seeking an in-person meeting following the COVID pandemic at the end of 2021, Genszler reached out to them. He wasn’t looking to have them as a tenant but as a sharer of space.

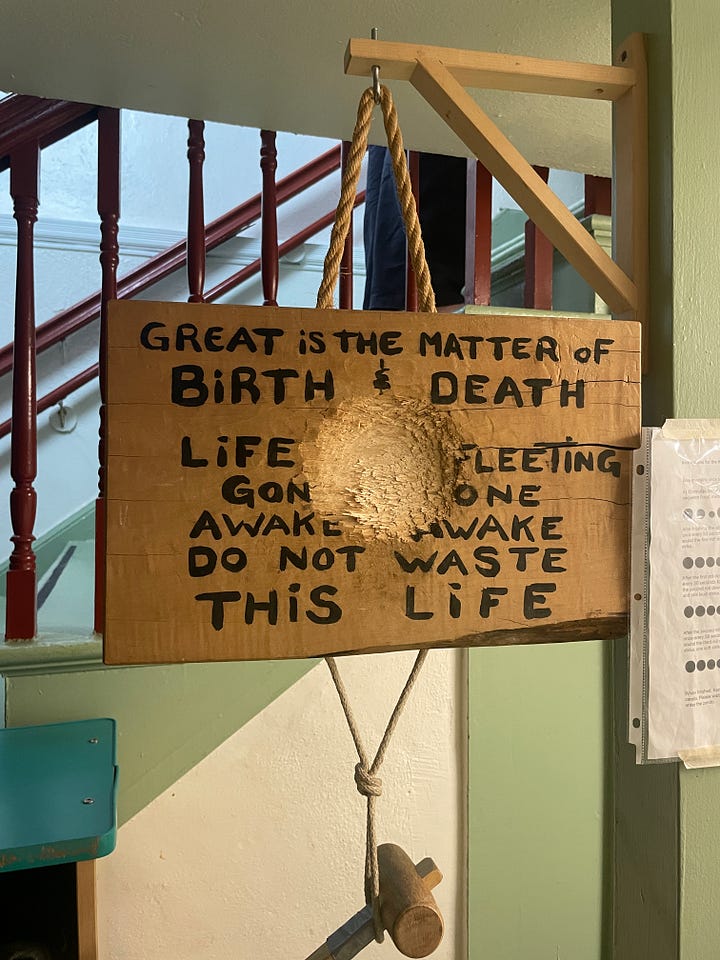

“Our primary places of practice are in two places within that building,” The Reverend explains, adding the Zen Center is based on the second floor while the Episcopal services are on the ground floor in what is known as the chapel. The Zen Center actually has two temples: its Brooklyn location, known as the Boundless Mind Temple, and another, Ancestral Heart Temple, located two hours north of New York City.

Sarah Dojin Emerson, a Zen priest and Dharma Teacher at the Brooklyn Zen Center, says moving its Boundless Mind Temple to Christ Church has been both a healing experience and an adjustment for the temple’s members.

“It’s been a cultural shift for our community to be in a non-dedicated space,” she says. “And a painful one for a number of people, and also a really cool learning in a way, of what it means to be in an interfaith space, a community space.”

One example of being in an interfaith space that Emerson likes to talk about is, how the incense between the Temple and Christ Church blend together on the stairwell, on some Sunday mornings. While the Episcopal service is happening on the first floor, the Temple may be having a retreat upstairs that is finishing up around noon. The incense from these two religious practices comes together.

“At first, people were like, we can’t do it when they’re there, and it’s like, no we can, actually,” Emerson says with a smile. “They are having service downstairs, even with music and we’re upstairs. It’s kind of wonderful.”

The healing Emerson mentions comes from what many at her temple experience for being allowed inside a church building despite being Buddhists. They may have their own space in the Christ Church building, but they are allowed to enter the doors, freely as they are. Some members of the Temple had previously felt marginalized by churches and some even hesitated to do their Buddhist practice at the Church Christ building.

“For some people, there’s pain,” she says. “They’d be like, ‘oh, I never want to be in a church again’. If they’re White Americans, they’re coming seeking Zen, usually because that wasn’t what they [had] grown up with.”

Reverend Genszler even notices that when younger Christians come for service, they also feel at ease.

“This is the sort of Christian practice that is unafraid,” he says. “That does not have a fearful stance toward the religious practice of others. And that is an attractive thing, an honest thing, a practical expression of reality…towards the phenomena of the world, towards New York City.”

Being unafraid means being open to not just the Brooklyn Zen Center, but other faiths. A Jewish afterschool program comes to Christ Church during the school year and this year, a progressive Muslim group celebrated Iftar during Ramadan. This all reflects the Reverend’s vision of Christ Church being a community center for the light of the world. He points out that many other Episcopalian churches share space with other churches; it’s just his church is “mission-adjacent”.

According to Genszler and Emerson, there were no objections from his congregation and the Brooklyn Zen Center when the two started sharing space, and the same goes for the other groups. Religious imagery would be put away in certain spaces, especially with groups that do not use any imagery would use those rooms.

Genszler says his church would not share space with another church or any other group that they disagree with in terms of conservative views in terms of sexuality, peace, and justice. He also says Episcopalians have a lot in common with the Zen Buddhist philosophy.

“I think there’s an increasing curiosity,” Reverend Genszler says. “There are a number of people of more than one community of practice. I know people who have a commitment to an Episcopal congregation but also practice with the Zen Center on Sunday. I don’t necessarily think that’s our aim now, although for both communities the door is certainly open to having Christian-Buddhist conversations.”

“Brooklyn is a wondrously diverse place,” Emerson says. “This leads to discussions on how wide inclusivity can be.”

Emerson adds that there is a need for buildings in New York that are meant for life, spirituality, faith, and community. However, there are barely any checks on that throughout the city.

“People need space for our lives,” she says. “And there seems to be very little check on that and whether the market demands. So, to me, it’s very transformational about Father Mark letting us in.”

On a quiet Sunday afternoon, just after a brief meeting with members of his congregation, following a service, Genszler talks about the repairs happening outside, at Christ Church’s exteriors, that also closed up the Nave, or the main church space. The Nave is the larger church space but is closed down for now as repairs take place overhead. For now, members of the Christ Church Episcopalian attend services in a small room known as the chapel. Other groups use this room too.

Reverend Genszler notes that the scaffolding outside nearly buries the church building itself, making some unable to see its 182-year-old history. But for Genszler, there is another meeting to it.

“This old building, surrounded by scaffolding, is like a metaphor of possibilities,” he said with satisfaction.

Based on what he has in mind for Christ Church Cobble Hill, he may not be wrong.